The most recent SLR photo cameras from Sony, the Sony Alpha 33 and Sony Alpha 55 are presenting a striking feature: a semi-transparent mirror replacing the usual reflex mirror that we knew up to now. This looks very nice in the press releases, what does that mean and why use such a technology?

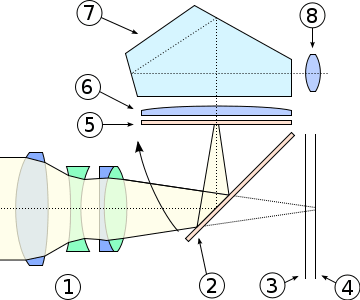

Cross-section view of SLR system:

1 – Front-mount lens (4-element Tessar design)

2 – Reflex mirror at 45-degree angle

3 – Focal plane shutter

4 – Film or sensor

5 – Focusing screen or glass

6 – Condenser lens

7 – Optical glass pentaprism (or pentamirror)

8 – Eyepiece

Origin: Wikipedia

The traditional SLR camera

Let’s start with the organization of the most common Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera, as we generally know it. On the cross-section view here, we can see the light trajectory (in yellow) when the mirror is in lower position to direct light (and the image) toward the viewfinder. At exposure time (when you press the shutter release button), the mirror moves up to let the light go straight to the sensor.

Very efficient, this configuration still has some drawbacks which have long been considered minor, but still very real.

First, during exposure, the viewfinder is totally black. It’s not very long, but the inconvenience is very observable by the user.

The mechanical design needed to move the mirror up and down is complex, fragile, but must operate very quickly to maintain a fast shooting cadence. On pro photo cameras, these mechanisms become complex and expensive to reach high frame rates. The technology progresses fast, but this is only in the most recent years that camera manufacturers have been able to provide more than 3 frames per second on standard cameras. Some pro SLRs (like the Nikon D3, for example) reach 8 fps (but the price falls in the financial investment category!)

Pellix – transparent or nearly transparent

In the 1960’s, several cameras started to use a semi-transparent mirror to avoid moving it. The idea is merely to ensure that most of the light goes straight to the film or the image sensor, but a smaller portion of it is reflected up to the viewfinder. Unsurprisingly, there are both advantages and drawbacks.

First pro: viewing is never obstructed. The photographer always keeps the camera at eye level and shoots nearly continuously (highly appreciated in sports photography, for example, to track unpredictable action).

Second pro: The removed mechanics allow to simplify the camera structure (and its cost). Light weight and low noise come to these cameras.

But the light splitting is difficult and the technology for semi-transparent mirrors is not easy to master: You want to keep transparency without the slightest color-shift (coming from the uneven transmission of all wavelengths), and without too much light loss (to have a clear and readable viewfinder, you must reflex as much light as possible, but this would be detrimental to the image exposure on the film).

The gains are perceptible but limited in front of the technical drawbacks: The market will not be convinced and, apart from random and rare occurrences like the Canon Pellix QL, this will be the end of it.

Autofocus & video

Then, come the 2000’s and point-and-shoot compact digital cameras start boasting about their video capture features. Always in search of technical innovations, camera manufacturers are happy to go from photo to video. It’s relatively easy on the a compact point-and-shoot: Either it has a separate telemetric viewfinder (no constraint), or the photo sensor is already used for LiveView (the only problem is that it engulf energy and heat the sensor up).

If you want to focus, the digital point-and-shoot cameras have a simple solution: Analyze the image on the sensor to see if it is sharp or not (this is called contrast detection). This seems simple, but it calls for a lot of computation power (this is slow) and you have to nearly randomly try various focus settings to find the best one.

On a cheap camera (or a cheaper camera that most Single Lens Reflex cameras), these drawbacks are easily forgotten and, moreover, the same approach works for video as well as for photography. So, the photo compact cameras have simple path to video capture.

An SLR with video

In 2008, Nikon decides to add video capture on a digital SLR (the Nikon D90). This should be marvelous! But the reflex architecture is totally different and there comes trouble.

First, when the mirror is up, it is impossible to use the specialized AF sensor that is present in the camera in front of the mirror, not behind (this sensor is using a method known as phase detection). The solution would appear to be easy: Go the point-and-shoot way, with contrast detection. But three problems rush in:

- SLR sensors are big and not very compatible with continuous heavy computation.

- SLR sensors are very large, favoring a small depth of field and are thus infinitely less tolerant than smaller/cheaper sensors (as a matter of fact, focusing on point-and-shoot cameras stay very imprecise, but it is efficiently hidden behind an enormous depth of field: “Everything always looks sharp”).

- The user is used to ultra-fast focusing given by phase detection, but will be hit with an enormous difference in reaction times.

The first SLR photo cameras choose to run around this problem by removing completely autofocus and most of the automated controls. Nothing elegant, nothing shiny here. But this is utterly pragmatic. And some pretty impressive cameras like the Canon EOS 5D MkII are equipped with very limited video features.

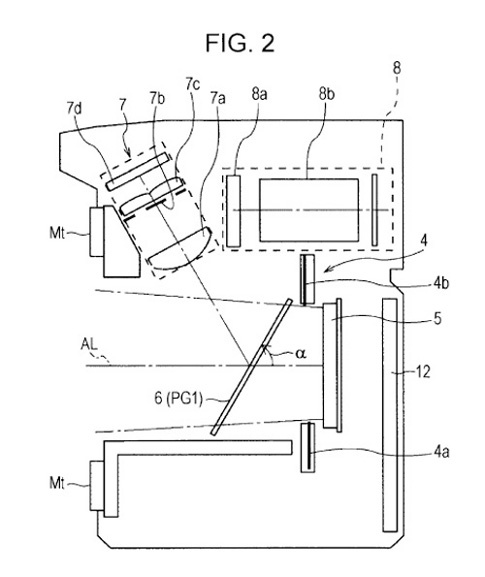

Sony Alpha SLT-A55

One exception in this landscape: Sony. Known as a historical leader of professional video, Sony cannot and will not deliver some half-baked video solution, even on a photo camera. They will only bring video capture when it is fully operational.

2010 is for Sony the year of solving this problem with a semi-transparent mirror again: Without mirror, all the troubles are gone! You can do autofocus while filming, you can keep nearly all the automated controls. The Sony Alpha 33 and Alpha 55 are entry-level photo cameras but their video capture is not relegated to the end of the feature list. Focusing is absolutely continuous during video filming (see the video demonstrations) or during continuous shooting.

Even better, on cameras priced at a few hundreds of Euros, it becomes possible to rush continuous shooting at incredible frame rates (at least out of the realm of expert and pro cameras): 6 frames per second! Or even 10 fps if you accept some constraints on available automatisms! This is comparable to what is offered by pro cameras at 10 times the price.

All this with a viewfinder permanently available. The clearer viewfinder you have, the more comfort you get.

And, if there is no longer any mirror moves, there is no longer any of the associated noises. Since the mirror mechanics generated very distinctive clangs just before and after the exposure, the cameras with a fixed mirror and remarkably silent.

Is it the end of it?

This is a good question. We understand that, now, the target is set very high. Canon, Nikon and the others competitors will be compared to a Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera sold under 600€. Innovation is now king in the Japanese (or not) Research and Development labs.

2011 will be a very interesting year for Sony’s opponents. Will they use the same recipe or will they bring some other bright idea to bring photo and video together in D-SLR cameras?

Comments

One response to “Why Sony uses a semi-transparent mirror in A33/A55”

I’ve tested the alpha55 at Photokina this week-end: I am impressed how fast it is